No. 92: Clémence Polès

Thinking about Iran, the Sofreh Haft-Seen of Nowruz, ’90s erotic thrillers, kyrgyz textiles, and the tenderness of the hammam.

Clémence Polès is a photographer and the founder of passerby, an online magazine known for its intimate portraits and glimpses into the homes (and minds) of everyday women. It’s a global project I’ve long admired for each woman featured and the guides gathered have one thing in common — true depth. Clémence was born in the south of France to an Iranian mother and a French father, and she grew up between Sharjah and Dubai, moving through a cultural intersection of Iranian, Arab, and Western influences. Her work weaves together photojournalism and portraiture, capturing the fine details of everyday life, the spaces we call home, and the intimate moments that reveal our identities. She’s currently working on her first book: a photographic archive of the Sofreh Haft Seen – the ceremonial table rooted in Zoroastrian tradition and set each year for Nowruz, the Persian New Year (more on this below!). From Clémence –

I. a place

As I write this, I’ll be honest—I can’t think of anything other than Iran right now.

Navigating fear, exhaustion, anxiety, and anger. Seeking tenderness amidst it all.

Reveling in distant, yet deeply familiar, memories of hiding in my grandfather’s bibliothèque in Tehran—floor-to-ceiling books, Persian rugs leaving no surface uncovered.

A tradition I seem to have carried with me across the different homes I’ve lived in.

Or in finding a second home in the bibliothèques of Paris. Like BULAC—Bibliothèque universitaire des langues et civilisations—where I once stumbled upon one of his books, published in 1977: فرهنگ علم اقتصادى انگليسى به فارسى / منوچهر فرهنگ

The first page holds one of his poems. One I return to often. One I love.

If I break my wings and feathers, I will lift my head to the sky.

And if you strike my cypress-like stem, I will cast my shadow upon this world.

I am the sea, and the wave that surges.

I am the cloud, and the cloud that climbs.

Ever in pursuit of knowledge

Ever in pursuit of knowledge

Politics often overtake the narrative of who Iranians are and what their culture is like, and so much of its beauty has been discarded because of that.

I find it wild that we’re at a point where we have to humanize that part of the world just to stir a flicker of sympathy—to remind others that these lives, too, are worthy of care, of continuity.

Contemplating the cloudy sky and the massive trunk of a tree under a magical light is difficult when one is alone. Not being able to feel the pleasure of seeing a magnificent landscape with someone else is a form of torture. That is why I started taking photographs. I wanted somehow to eternalize those moments of passion and pain.

—Abbas Kiarostami

II. a 3000 year old tradition

I’ve always been drawn to Nowruz—not just because it’s a 3,000-year-old tradition that has survived the rise and fall of empires, religions, and borders, or because 300 million people around the world still celebrate it each spring equinox. But because it’s been carried on, quietly and powerfully, by women. And it still is.

Each ritual feels like a reset, mirroring the planet’s own shift into spring. One of the most beautiful parts of Nowruz is the Sofreh Haft-Seen—a table set with seven symbolic items, each starting with the letter “S” in Persian. It’s both visually striking and deeply meaningful.

No two Haft-Seens are alike. From the vessels that hold the items to the way the table is arranged, it’s all incredibly personal. I’ve always seen them as temporary art installations—quiet, thoughtful self-portraits created mostly by women, year after year.

For me, setting up my Sofreh is how I close out the year. After the ritual spring cleaning we call khāne-takānī (“shaking the house”), I’ll put on some Marjan or Googoosh, and carefully arrange each element as a symbolic reminder of renewal.

III. a film genre

I love a ’90s erotic thriller—or an “infidelity thriller,” as I like to call them. There’s usually a kind of meditation that accompanies each shot, an attention to seemingly meaningless details that I don’t often see in contemporary thrillers. Louis Malle’s Damage, starring a young Juliette Binoche and Jeremy Irons, really hits the spot. The plot is your typical patriarchal ’90s setup, but the cinematography alone makes it worth watching. And Miranda Richardson’s performance at the end? That’s not usually something I care about, but damn—it’s award-worthy.

Jade and Body Heat are recent additions to my Best Erotic Films list. I’ve been in a bit of a fashion rut, but Linda Fiorentino in Jade pulled me out of it. That dress looks like something from Khaite or Paris Georgia. And the skirt suit—paired with the collar, the pearls, the sunglasses? Oof.

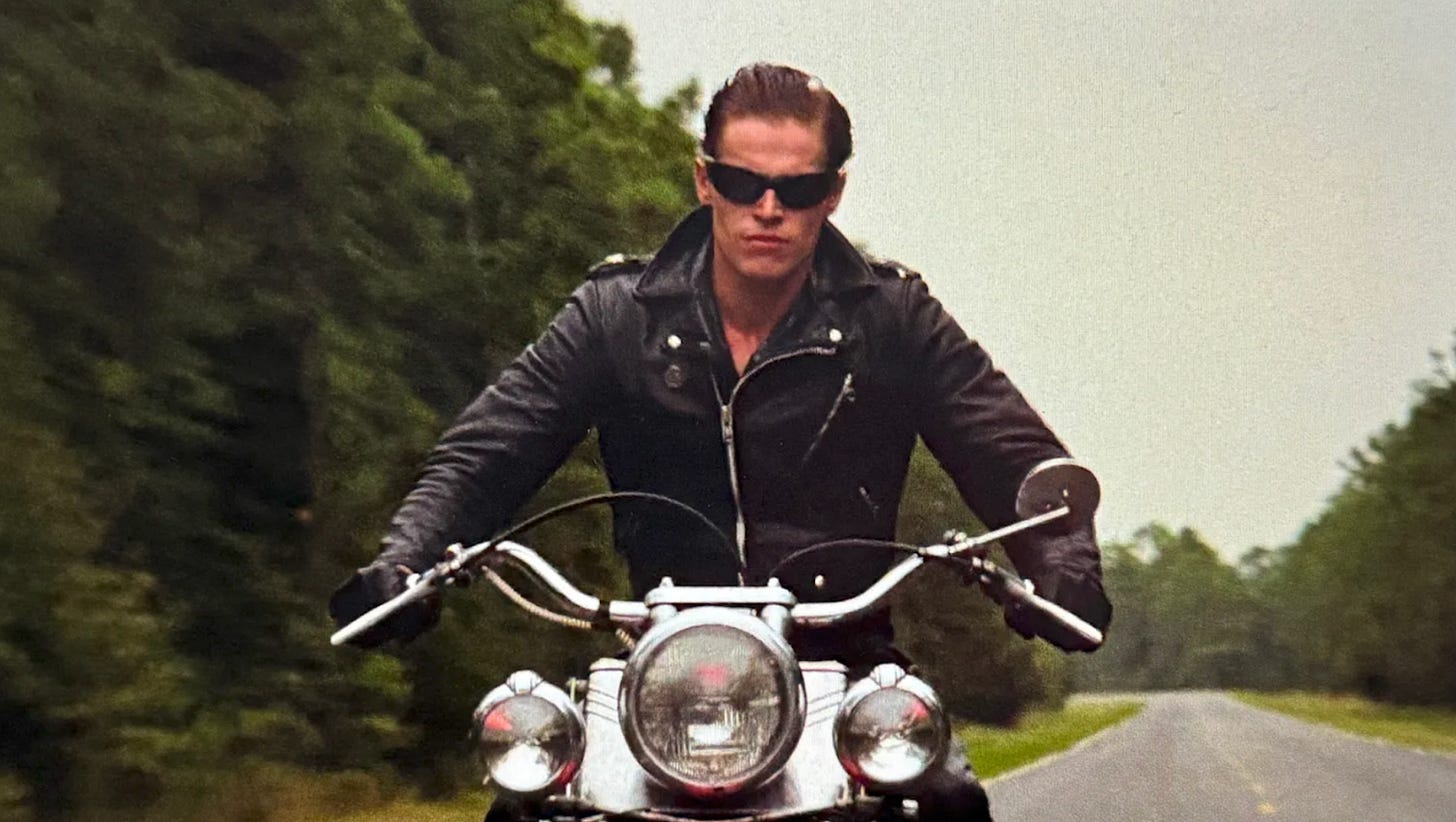

I’ve also been rediscovering my love for technothrillers, which could be considered a subgenre of erotic thrillers, like New Rose Hotel by Abel Ferrara. Speaking of Willem Dafoe… The Loveless by Kathryn Bigelow is such a hidden erotic gem.

As a teenager, I’d watch Strange Days and Demonlover on repeat; I remember getting bootleg VHS copies. Demonlover was the closest thing I had to porn.

Looking back, I wonder if that fixation had something to do with growing up in Dubai in the early ’90s—a place that felt futuristic, yet strangely hollow.

IV. a kyrgyz textile

I recently traveled to Kyrgyzstan for the first time to photograph traditional felt-making and the women who carry this craft forward.

On my first day in Bishkek, I was taken to the Museum of Fine Arts, where I found myself in front of a wall of Kyrgyz textiles—shyrdak, ala-kiyiz, tush kyiz.

I’ve grown up with Persian rug culture, but this was something else entirely.

I hadn’t realized how integral textiles are to Kyrgyz culture, or how much they communicate. The design elements are not mere decoration, but signifiers understood and interpreted through a shared cultural literacy. The tush kyiz often takes women years to complete and are not for sale—they're passed down as family heirlooms, stitched with blessings, pride, and symbols of Kyrgyz life.

This language of textiles extends into clothing and jewelry as well. Patterns and garments can signal whether a woman is married, has children, or what region she comes from. Headdresses like the elechek or jooluk indicate marital status, while embroidered aprons like the beldemchi, gifted after childbirth, symbolize protection and maternal pride. Even the materials and trims—fur, felt, stitching—reflect social standing.

One artist that struck me in the whole museum was the work of Akhmatova Raykul Shaimukhametovna (Ахматова Райкуль Шаймухаметовна), who sadly passed away in 2023.

There isn’t even a Wikipedia page for her, which is insane, but our tour guide told us she was a highly respected Kyrgyz applied artist and teacher, renowned for her modern reinterpretation of traditional felt art. There’s a quiet intensity in her work—something between landscape and memory, figure and myth, craft and art.

I must add, all this was displayed against the backdrop of a monumental Brutalist building, which was built in the 1970s. The museum was conceived as a total work of art, where even the structure itself could be read as part of the exhibition.

V. a realm of care and tenderness

My first hammam experience was in 2022, at La Mosquée de Paris. No one explained how things worked or what I was supposed to do. But to my surprise, the women around me immediately stepped in to help, without having to be asked.

One woman offered to rub orange blossom soap onto my back, explaining that her grandmother in Morocco had made it: “The scent will stay and soothe you all day,” she said. Another called over a woman to scrub me, noting she had a gentler touch.

Micro-moments of tenderness, in the nude.

I had stumbled into one of the most welcoming communities of women I’d ever encountered.

Historically, this makes sense. Communal bathing has existed for centuries, but in much of the Islamic world, the hammam became a rare space where women could meet, talk, and care for one another. It was where rituals were passed down—woman to woman, gesture by gesture.

It wasn’t until I visited Istanbul that I was introduced to other hammam traditions. At the Kılıç Ali Pasha Hammam—one of the city’s most iconic and well-preserved bathhouses—I experienced the classical Turkish style firsthand.

Built in the late 16th century, it was part of a larger complex with a mosque and school, commissioned by Kılıç Ali Pasha, a former Italian who converted to Islam and rose to prominence in the Ottoman Empire.

Until then, I’d only known the Moroccan version: smaller, neighborhood bathhouses with dense steam, black soap, and a vigorous scrub.

This, by contrast, felt slower, more ceremonial. The scrub was only the beginning. Lying on a heated marble slab, you watch as the natır swings a cloth called a torba through the air, releasing a cloud of bubbles that collapse onto your body. The motion is precise—almost like a dance. You’re floating in a layer of silky foam, while across the room, women sit hunched forward, then rise, wrapped in bubbles. We’re all suspended in a kind of bliss, as if existing briefly in another realm.

BULLETIN

Los Angeles

On view: Group show Glawr opens Saturday at Hannah Hoffman Gallery. James Varvaise and Henry Taylor’s Sometimes a Straight Line Has to Be Crooked at Hauser & Wirth. Matt Bollinger’s Homecoming at Francois Ghebaly. Noah Davis survey at the Hammer. Oliver Clegg’s Always Right, Sometimes Left at Journal Gallery. Justin John Greene’s Particular Dish at Matthew Brown. Hannah Lee’s Dumbo’s Feathers at James Fuentes. Lucas Rubly’s Monumentos à Memória at Sea View. Kaoru Ueda at Nonaka Hill. Richard Diebenkorn: The 1993 Portfolio at Gemini G.E.L. Adam Silverman’s Seeds and Weeds, Tomoo Gokita’s Naked, Sarah Rosalena’s Unending Spiral, Wilhelm Sasnal’s AAAsphalt at Blum. Mungo Thomson’s Time Life and Nathaniel Oliver’s A Tension Worth Keeping Because the Drift is Always There at Karma. Alan Lynch’s Infinitely on the Surfaces of This Teardrop World at Chateau Shatto. Henry Churchod’s Rome Is No Longer in Rome at Clearing. JJ Manford’s Jacaranda June at Nazarian/Curcio. Group show The Abstract Future at Jeffrey Deitch. Group show Flower Hour at Authorized Dealer.

New York

On view: Group show The Calling of Home at Tina Kim. Making Home—Smithsonian Design Triennial at The Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian. Sam Francis’ Where Color Begins: Works on Paper at Hollis Taggart. Juanita McNeely’s Works on Paper at James Fuentes. Wenhui Hao’s By The Rivers Dark and group show French Fry’s Fifth at Half Gallery. Diane Arbus: Constellation at the Park Avenue Armory. Koichi Sato’s Adolescent Sanctuary at 56 Henry. Isabella Ducrot’s Visited Lands at Petzel. Jenny Calivas: Self Portraits While Buried and Maria Antelman’s Conjurer at Yancey Richardson. Lorna Simpson’s Source Notes at The Met. Toshiko Takaezu’s Bronzes at James Cohan. Alexis Ralaivao’s Éloge de l’ombre at Kasmin. Semiotics of Dressing at Jacqueline Sullivan. Austin Weiner’s Half Way Home at Levy Gorvy Dayan. Group show Circa 1995 at Zwirner. Leiko Ikemura’s Talk to the Sky, Seeking Light at Lisson. Salman Toor’s Wish Maker at Luhring Augustine. William Kentridge’s A Natural History of the Studio and Eternal Beginnings: Francis Picabia at Hauser & Wirth. Sargent and Paris at The Met. Jack Whitten: The Messenger and Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers at MoMa. Louise Nevelson’s Collection View at The Whitney.

From the archives, lately:

Affection Archives is a weekly look into the affections of yours truly (Arielle Eshel) & people I admire.

Thank you for having me 🌹

Enjoyed this immensely!